Computational Thinking (CT) is becoming a fundamental literacy skill, such as reading and writing, and expected to be used worldwide by the middle of the century. CT is “the thought process involved in formulating a problem and expressing it in a way that a computer - human or machine - can effectively carry out”. It borrows concepts from computer science, such as sequences, operators, and iteration as well as practices like being incremental and iterative, testing, debugging, abstracting, and reusing.

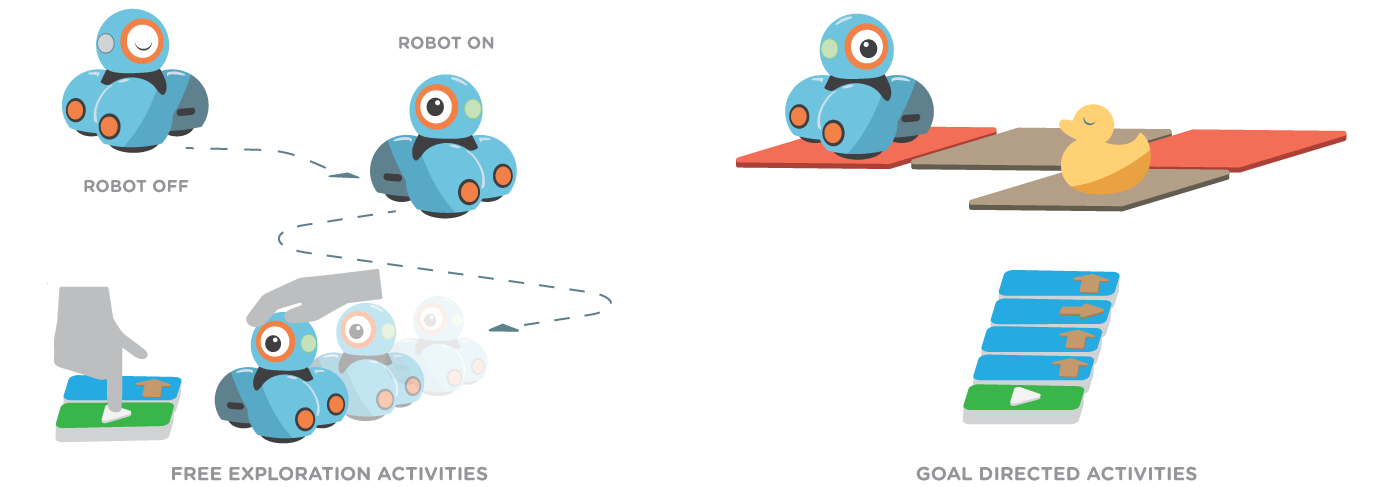

This project investigates the use of tangible block-based systems accessible to children with visual impairments to perform programming activities alongside their sighted peers and family. Unlike previous work that us mostly limited to building sequential audio-based actions, we explore the use of small robots in spatial programming activities.

Project Details

Title: Inclusive Computational Thinking

Date: Apr 9, 2020

Authors: Hugo Nicolau, Tiago Guerreiro, Ana Pires, Isabel Neto, Filipa Rocha, Diana Mendes

Keywords: inclusion, computational thinking, robots

Related Publications

- Exploring Collaboration in Programming Activities with Children with Visual Impairments: a 10-Session Study in a School Setting

- Filipa Rocha, David Gonçalves, Ana Cristina Pires, Hugo Nicolau, and Tiago Guerreiro. 2025. Exploring Collaboration in Programming Activities with Children with Visual Impairments: a 10-Session Study in a School Setting. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 9, 2. http://doi.org/10.1145/3710971

- [ABSTRACT] [PDF] [LIBRARY]

Introductory coding environments have been used in early education to promote computational thinking, supporting the development of cognitive, critical, and social skills. Many environments focus on individual use, which has limited benefits compared to collaborative learning. In this paper, we present the results of a 10-session study at a local primary school engaging eleven children with visual impairments and three inclusive education teachers in collaborative programming activities. Based on participants’ behavior, reactions, and feedback, we contribute an improved understanding of collaborative design in educational settings, focusing on the impact of Goals, Workspace, Interdependence, and Shared Awareness. Our main findings outline how collaboration dynamics can be shaped by asymmetric tasks, workspace proximity, and group awareness. We further discuss factors that led to a lack of investment in the shared goal and instances of unbalanced collaboration, reflecting on challenges and opportunities for designing collaborative inclusive coding kits.

- Awareness in Collaborative Mixed-Visual Ability Tangible Programming Activities

- Filipa Rocha, Hugo Simão, João Nogueira, Isabel Neto, Tiago Guerreiro, and Hugo Nicolau. 2025. Awareness in Collaborative Mixed-Visual Ability Tangible Programming Activities. Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Association for Computing Machinery. http://doi.org/10.1145/3706598.3713610

- [ABSTRACT] [PDF] [LIBRARY]

In the context of computational thinking tasks, which often require problem-solving and critical thinking skills, awareness of a partner’s actions can play a significant role in fostering a balanced collaboration. Understanding how awareness influences mixed-visual ability group collaboration in a tangible environment can provide insights into inclusive design for learning environments. To address this issue, we ran a user study where 6 mixed-visual ability pairs engaged in a tangible programming activity. The study had three experimental conditions, representing 3 different levels of awareness. Our findings reveal that while pre-existing power dynamics heavily influenced collaboration, workspace awareness feedback was essential in fostering engagement and improving communication for both children. This paper highlights the need for designing inclusive collaborative programming systems that account for workspace awareness and individual abilities, offering insights into more effective and balanced collaborative environments.

- Ethical Concerns when Working with Mixed-Ability Groups of Children

- Ana O Henriques, Patricia Piedade, Filipa Rocha, Isabel Neto, and Hugo Nicolau. 2024. Ethical Concerns when Working with Mixed-Ability Groups of Children. Proceedings of the 26th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Association for Computing Machinery. http://doi.org/10.1145/3663548.3675648

- [ABSTRACT] [PDF] [LIBRARY]

Accessibility research has gained traction, yet ethical gaps persist in the inclusion of individuals with disabilities, especially children. Inclusive research practices are essential to ensure that research and design solutions cater to the needs of all individuals, regardless of their abilities. Working with children with disabilities in Human-Computer Interaction and Human-Robot Interaction presents a unique set of ethical dilemmas. These young participants often require additional care, support, and accommodations, which can fall off researchers’ resources or expertise. The lack of clear guidance on navigating these challenges further aggravates the problem. To provide a basis on which to address this issue, we adopt a critical reflective approach, evaluating our impact by analyzing two case studies involving children with disabilities in HCI/HRI research. Flowing from these, we call for a shift in our approach to ethics in participatory research contexts to one that is processual, situational, and community-led.

- Coding Together: On Co-located and Remote Collaboration between Children with Mixed-Visual Abilities

- Filipa Rocha, Filipa Correia, Isabel Neto, et al. 2023. Coding Together: On Co-located and Remote Collaboration between Children with Mixed-Visual Abilities. Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Association for Computing Machinery. http://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581261

- [ABSTRACT] [PDF] [LIBRARY]

Collaborative coding environments foster learning, social skills, computational thinking training, and supportive relationships. In the context of inclusive education, these environments have the potential to promote inclusive learning activities for children with mixed-visual abilities. However, there is limited research focusing on remote collaborative environments, despite the opportunity to design new modes of access and control of content to promote more equitable learning experiences. We investigated the tradeoffs between remote and co-located collaboration through a tangible coding kit. We asked ten pairs of mixed-visual ability children to collaborate in an interdependent and asymmetric coding game. We contribute insights on six dimensions - effectiveness, computational thinking, accessibility, communication, cooperation, and engagement - and reflect on differences, challenges, and advantages between collaborative settings related to communication, workspace awareness, and computational thinking training. Lastly, we discuss design opportunities of tangibles, audio, roles, and tasks to create inclusive learning activities in remote and co-located settings

- Ethical Concerns when Working with Mixed-Ability Groups of Children

- Patricia Piedade, Ana Henriques, Filipa Rocha, Isabel Neto, and Hugo Nicolau. 2023. Ethical Concerns when Working with Mixed-Ability Groups of Children. In Proceedings of ASSETS 2023 Workshop - Tackling the Lack of a Practical Guide in Disability-Centered Research. Retrieved from https://assets2023guide.mere.st/accepted-submissions/

- [ABSTRACT] [PDF] [LIBRARY]

Accessibility research has gained traction, yet ethical gaps persist in the inclusion of individuals with disabilities, especially children. Inclusive research practices are essential to ensure research and design solutions cater to the needs of all individuals, regardless of their abilities. Working with children with disabilities in Human-Computer Interaction and Human-Robot Interaction presents a unique set of ethical dilemmas. These young participants often require additional care, support, and accommodations, which can fall off researchers’ resources or expertise. The lack of clear guidance on navigating these challenges further aggravates the problem. To provide a base and address this issue, we adopt a critical reflective approach, evaluating our impact by analyzing two case studies involving children with disabilities in HCI/HRI research.

- TACTOPI: Exploring Play with an Inclusive Multisensory Environment for Children with Mixed-Visual Abilities

- Ana Cristina Pires, Lúcia Verónica Abreu, Filipa Rocha, et al. 2023. TACTOPI: Exploring Play with an Inclusive Multisensory Environment for Children with Mixed-Visual Abilities. Proceedings of the 22nd Annual ACM Interaction Design and Children Conference, Association for Computing Machinery, 411–422. http://doi.org/10.1145/3585088.3589389

- [ABSTRACT] [PDF] [LIBRARY]

Playful robotics engages children in learning through play experiences while simultaneously developing critical thinking, and social, cognitive, and motor skills through play. Such playful experiences are particularly valuable in inclusive education to promote social and inclusive behaviors. We present TACTOPI, an inclusive and playful multisensory environment that leverages tangible interaction and a robot as the main character. We investigate how TACTOPI supports play in 10 dyads of children with mixed visual abilities. Results show that multisensory elements supported children to experience activities as joyful. Storytelling and guided-play added a layer of meaningfulness to the activities, and the robot engaged children in minds-on thinking. TACTOPI afforded children to engage in collaborative social play and facilitated supportive and inclusive behaviours. We contribute with a playful multisensory environment, an analysis of the effect of its components on social, cognitive, and inclusive play, and design considerations for inclusive multisensory environments that prioritize play.

- Current Practices in Teaching Computational Thinking to Children: Accessibility as an Afterthought

- Marta Carvalho, Filipa Rocha, João Guerreiro, Hugo Nicolau, Tiago Guerreiro, and Ana C. Pires. 2022. Current Practices in Teaching Computational Thinking to Children: Accessibility as an Afterthought. IDC Workshop on Co-designing with Mixed-ability Groups of Children to Promote Inclusive Education.

- [ABSTRACT] [PDF]

Recognition of computational thinking as a relevant skill set has increased its prevalence in school curricula, and the number of coding platforms and kits available. The inaccessibility of the latter has been a focus of recent attention resulting in the emergence of accessible approaches. Conversely, there has been limited attention to activities, how training platforms are being used in curricular practice, and how they are being adapted for children with disabilities. We present findings from a qualitative interview study with 6 IT instructors depicting their practices, experiences, and their views towards an inclusive future classroom.

- Accembly at Home: Accessible Spatial Programming for Children with Visual Impairments and Their Families

- Filipa Rocha, Ana Cristina Pires, Isabel Neto, Hugo Nicolau, and Tiago Guerreiro. 2021. Accembly at Home: Accessible Spatial Programming for Children with Visual Impairments and Their Families. Interaction Design and Children, Association for Computing Machinery, 100–111. http://doi.org/10.1145/3459990.3460699

- [ABSTRACT] [PDF] [LIBRARY]

Accessible introductory programming environments are scarce, and their study within ecological settings (e.g., at home) is almost non-existent. We present ACCembly, an accessible block-based environment that enables children with visual impairments to perform spatial programming activities. ACCembly allows children to assemble tangible blocks to program a multimodal robot. We evaluated this approach with seven families that used the system autonomously at home. Results showed that both the children and family members learned from what was an inclusive and engaging experience. Children leveraged fundamental computational thinking concepts to solve spatial programming challenges; parents took different roles as mediators, some actively teaching and scaffolding, others learning together with their child. We contribute with an environment that enables children with visual impairments to engage in spatial programming activities, an analysis of parent-child interactions, and reflections on inclusive programming environments within a shared family experience.

- Exploring Accessible Programming with Educators and Visually Impaired Children

- Ana Cristina Pires, Filipa Rocha, Antonio José de Barros Neto, Hugo Simão, Hugo Nicolau, and Tiago Guerreiro. 2020. Exploring Accessible Programming with Educators and Visually Impaired Children. Proceedings of the Interaction Design and Children Conference, Association for Computing Machinery, 148–160. http://doi.org/10.1145/3392063.3394437

- [ABSTRACT] [PDF] [LIBRARY]

Previous attempts to make block-based programming accessible to visually impaired children have mostly focused on audio-based challenges, leaving aside spatial constructs, commonly used in learning settings. We sought to understand the qualities and flaws of current programming environments in terms of accessibility in educational settings. We report on a focus group with IT and special needs educators, where they discussed a variety of programming environments for children, identifying their merits, barriers and opportunities. We then conducted a workshop with 7 visually impaired children where they experimented with a bespoke tangible robot-programming environment. Video recordings of such activity were analyzed with educators to discuss children’s experiences and emergent behaviours. We contribute with a set of qualities that programming environments should have to be inclusive to children with different visual abilities, insights for the design of situated classroom activities, and evidence that inclusive tangible robot-based programming is worth pursuing.